Abstract

The formation of strongly correlated fermion pairs is fundamental for the emergence of fermionic superfluidity and superconductivity1. For instance, Cooper pairs made of two electrons of opposite spin and momentum at the Fermi surface of the system are a key ingredient of Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory—the microscopic explanation of the emergence of conventional superconductivity2. Understanding the mechanism behind pair formation is an ongoing challenge in the study of many strongly correlated fermionic systems3. Controllable many-body systems that host Cooper pairs would thus be desirable. Here we directly observe Cooper pairs in a mesoscopic two-dimensional Fermi gas. We apply an imaging scheme that enables us to extract the full in situ momentum distribution of a strongly interacting Fermi gas with single-particle and spin resolution4. Our ultracold gas enables us to freely tune between a completely non-interacting, unpaired system and weak attractions, where we find Cooper pair correlations at the Fermi surface. When increasing the attractive interactions even further, the pairs gradually turn into deeply bound molecules that break up the Fermi surface. Our mesoscopic system is closely related to the physics of nuclei, superconducting grains or quantum dots5,6,7. With the precise control over the interactions, particle number and potential landscape in our experiment, the observables we establish in this work provide an approach for answering longstanding questions concerning not only such mesoscopic systems but also their connection to the macroscopic world.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yang, C. N. Concept of off-diagonal long-range order and the quantum phases of liquid He and of superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 34, 694–704 (1962).

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N. & Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

Zhou, X. et al. High-temperature superconductivity. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 462–465 (2021).

Holten, M. et al. Observation of Pauli crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 020401 (2021).

Alhassid, Y. The statistical theory of quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 895–968 (2000).

von Delft, J. Superconductivity in ultrasmall metallic grains. Ann. Phys. 10, 219–276 (2001).

Launey, K. (ed.) Emergent Phenomena in Atomic Nuclei from Large-scale Modeling : A Symmetry-Guided Perspective (World Scientific, 2017).

Altman, E., Demler, E. & Lukin, M. D. Probing many-body states of ultracold atoms via noise correlations. Phys. Rev. A 70, 013603 (2004).

Schweigler, T. et al. Experimental characterization of a quantum many-body system via higher-order correlations. Nature 545, 323–326 (2017).

Flammia, S. T., Gross, D., Liu, Y.-K. & Eisert, J. Quantum tomography via compressed sensing: error bounds, sample complexity and efficient estimators. New J. Phys. 14, 095022 (2012).

Zache, T. V., Schweigler, T., Erne, S., Schmiedmayer, J. & Berges, J. Extracting the field theory description of a quantum many-body system from experimental data. Phys. Rev. 10, 011020 (2020).

Cooper, L. N. Bound electron pairs in a degenerate Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. 104, 1189–1190 (1956).

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X.-G. Doping a Mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17–85 (2006).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885–964 (2008).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Nascimbène, S. Quantum simulations with ultracold quantum gases. Nat. Phys. 8, 267–276 (2012).

Greiner, M., Regal, C. A., Stewart, J. T. & Jin, D. S. Probing pair-correlated fermionic atoms through correlations in atom shot noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 110401 (2005).

Fölling, S. et al. Spatial quantum noise interferometry in expanding ultracold atom clouds. Nature 434, 481–484 (2005).

Rom, T. et al. Free fermion antibunching in a degenerate atomic Fermi gas released from an optical lattice. Nature 444, 733–736 (2006).

Spielman, I., Phillips, W. & Porto, J. Mott-insulator transition in a two-dimensional atomic Bose gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 080404 (2007).

Jeltes, T. et al. Comparison of the Hanbury Brown–Twiss effect for bosons and fermions. Nature 445, 402–405 (2007).

Tenart, A., Hercé, G., Bureik, J.-P., Dareau, A. & Clément, D. Observation of pairs of atoms at opposite momenta in an equilibrium interacting Bose gas. Nat. Phys. 17, 1364–1368 (2021).

Bakr, W. S., Gillen, J. I., Peng, A., Fölling, S. & Greiner, M. A quantum gas microscope for detecting single atoms in a Hubbard-regime optical lattice. Nature 462, 74–77 (2009).

Sherson, J. F. et al. Single-atom-resolved fluorescence imaging of an atomic Mott insulator. Nature 467, 68–72 (2010).

Parsons, M. F. et al. Site-resolved measurement of the spin-correlation function in the Fermi–Hubbard model. Science 353, 1253–1256 (2016).

Koepsell, J. et al. Robust bilayer charge pumping for spin- and density-resolved quantum gas microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 010403 (2020).

Bergschneider, A. et al. Spin-resolved single-atom imaging of 6Li in free space. Phys. Rev. A 97, 063613 (2018).

Preiss, P. M. et al. High-contrast interference of ultracold fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 143602 (2019).

Bayha, L. et al. Observing the emergence of a quantum phase transition shell by shell. Nature 587, 583–587 (2020).

Serwane, F. et al. Deterministic preparation of a tunable few-fermion system. Science 332, 336–338 (2011).

Zürn, G. et al. Precise characterization of 6Li Feshbach resonances using trap-sideband-resolved RF spectroscopy of weakly bound molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 135301 (2013).

Randeria, M., Duan, J.-M. & Shieh, L.-Y. Superconductivity in a two-dimensional Fermi gas: evolution from Cooper pairing to Bose condensation. Phys. Rev. B 41, 327–343 (1990).

Bohr, A. & Mottelson, B. R. Nuclear Structure Vols I, II (W.A. Benjamin, 1975).

Bruun, G. M. Long-lived Higgs mode in a two-dimensional confined Fermi system. Phys. Rev. A 90, 023621 (2014).

Bjerlin, J., Reimann, S. & Bruun, G. Few-body precursor of the Higgs mode in a Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 155302 (2016).

Randeria, M., Duan, J.-M. & Shieh, L.-Y. Bound states, Cooper pairing, and Bose condensation in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 981–984 (1989).

Asteria, L., Zahn, H. P., Kosch, M. N., Sengstock, K. & Weitenberg, C. Quantum gas magnifier for sub-lattice-resolved imaging of 3D quantum systems. Nature 599, 571–575 (2021).

Murthy, P. A. et al. High-temperature pairing in a strongly interacting two-dimensional Fermi gas. Science 359, 452–455 (2017).

Pecak, D. & Sowiński, T. Signatures of unconventional pairing in spin-imbalanced one-dimensional few-fermion systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 012077 (2020).

Chevy, F. & Mora, C. Ultra-cold polarized Fermi gases. Rep. Prog. Phys. 73, 112401 (2010).

Palm, L., Grusdt, F. & Preiss, P. M. Skyrmion ground states of rapidly rotating few-fermion systems. New J. Phys. 22, 083037 (2020).

Pecci, G., Naldesi, P., Minguzzi, A. & Amico, L. The phase of a degenerate Fermi gas. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.10408 (2021).

Idziaszek, Z. & Calarco, T. Analytical solutions for the dynamics of two trapped interacting ultracold atoms. Phys. Rev. A 74, 022712 (2006).

Zwierlein, M. W. High-Temperature Superfluidity in an Ultracold Fermi Gas. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2007).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge discussions with A. Faribault and J. von Delft. This work has been supported in parts by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation): the Collaborative Research Centre SFB 1225 (ISOQUANT) and Germany’s Excellence Strategy EXC2181/1-390900948 (the Heidelberg STRUCTURES Excellence Cluster). It was also funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 817482 (PASQuanS) and no. 725636 (QuStA). We also acknowledge support by the Heidelberg Center for Quantum Dynamics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., L.B. and K.S. performed the measurements. M.H., L.B., K.S. and S.B. analysed the data. C.H. and M.H. performed the numerical calculations. P.L. set up the phase-locked loop for the Raman beams. P.M.P. and S.J. supervised the project. M.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Grigori Astrakharchik, Servaas Kokkelmans and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

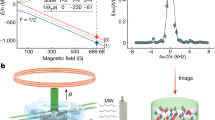

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sketch of the TOF imaging sequence.

a, The TOF imaging scheme is initiated by switching off the trapping potential and the interparticle interactions. To this end, we shine in two copropagating Raman laser beams to quasi-instantaneously transfer all atoms from state |3⟩ to state |4⟩ (step 1). After the Raman transition, we ramp the magnetic field from the value B0 that sets the in situ interaction strength to a constant value of B = 750 where the fidelity of the following spin flips is maximal. Only the imaging transitions of state |3⟩ and |6⟩ are closed. Two successive radio frequency (RF) Landau–Zener sweeps are applied to move all the atoms from state |1⟩ to |3⟩ during the free expansion (steps 2, 3). This is followed by taking the first image with illumination beams that are resonant only to state |3⟩ (step 4). Before taking the second image, a microwave (MW) Landau–Zener sweep transfers the remaining atoms in |4⟩ to state |3⟩ again (steps 5, 6). The microwave pulse leads to higher transfer fidelities than the Raman lasers but is much slower. b, The duration of the initial Raman flip with Tπ = 300 ns is chosen as fast as technically possible to prevent any scattering between atoms from occurring during the expansion. The radio frequency flips are solely optimized for transfer fidelities and are distributed over the remaining time of TTOF = 9 ms. The time of the microwave flip is set by the maximal frame rate of the camera. c, From a single experimental run we obtain two binary images where bright pixels indicate that at least one photon hit the chip at this location. In the first step we apply a low-pass filter to these images. A simple peak detection with an optimized acceptance threshold then allows us to extract the position of all spin-up and spin-down particles.

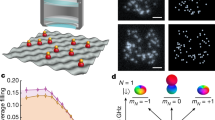

Extended Data Fig. 2 Different particle numbers.

In our experiment, we are able to prepare closed- and open-shell configurations with different particle numbers. a–c, Single momentum space projections of the three lowest closed-shell ground states with 3 + 3 (a), 6 + 6 (b) and 10 + 10 (c) particles. The dashed circle indicates the corresponding Fermi momentum for each particle number. d, The total weight in the pair-correlation peak of \({{\mathscr{C}}}_{\uparrow }^{(2)}\) is plotted versus particle number and for the setting where the reference particle is fixed at the Fermi surface (for 6 + 6, see Fig. 2h). We find that the absolute number of paired atoms increases, and their fractions remain approximately constant from N = 3 + 3 to N = 10 + 10 particles. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Scanning the interaction switch-off time.

Tπ is the duration of the spin flip from a strongly interacting |1⟩–|3⟩ to an (almost) non-interacting |1⟩–|4⟩ mixture at the beginning of the TOF sequence (inset). When we increase Tπ, the magnitude of the pair correlations reduces greatly above a threshold of Tπ = 100 μs (red circles). The reason is that scattering events during the TOF expansion redistribute the momenta between the participating atoms and destroy the correlations that were present between the in situ momenta. We model the effect by assuming that each scattering event between two atoms annihilates all the in situ correlations for those particles. The only parameters that enter the model (solid line) are the scattering rate λsc of the |1⟩–|3⟩ mixture at the magnetic offset field (B0 = 750) and the in situ density. The dashed line shows the same model prediction but at one of the highest scattering rates used in our experiments (B0 = 695, EB/ħωr = 1.97). It follows that at the spin flip time of Tπ = 300 ns that we use for our experiments, no scattering is expected to occur during the TOF at any interaction strength setting. The mean kinetic energies Ekin (blue squares) show a similar dependence on Tπ. This indicates again that only for Tπ ≪ 1/λsc (with λsc ≲ 50 kHz) the true in situ momentum distribution is obtained after the TOF sequence. The error bars are obtained from the counts in each bin of the momentum distribution and the correlation function respectively and by assuming Poissonian statistics.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Single-atom detection fidelity.

The raw images are analysed by first applying a low-pass filter followed by a simple peak-detection algorithm. A histogram of the amplitudes of all detected peaks in 2,000 images of a single spin component is plotted. We find a bimodal distribution. The maximum at low amplitudes originates from background noise of the camera. The second maximum at higher amplitudes is due to real photon clusters on the chip. Every peak with an amplitude above the threshold (vertical black line) is counted as an atom. This leads to single-atom detection fidelities of 97.8(9)%. There is a probability of 5.0(5)% for a false positive detection of an atom on each image for our chosen region of interest of 320 × 320 px. For 6 + 6 atoms this leads to a rate of false-to-true detections of 0.83(10)%. The solid red and blue lines are Gaussian and exponential fits to the data, respectively, and the dashed line is their sum.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Collection of 28 single momentum-space projections taken at EB/ħωr = 1.97.

The images have been postselected for the correct particle number of the 6 + 6 ground state but are otherwise chosen randomly. The dashed circles indicate the Fermi momentum. Atoms pairs with Δϕ < 30° and p↑ and p↓ larger than 2/3pF are highlighted. These are the particles that contribute to the pair-correlation peak at the Fermi surface (see Fig. 2i). We find considerably more such pairs in images taken at larger interaction strengths (compare Extended Data Fig. 6).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Collection of 28 single momentum-space projections taken at EB/ħωr = 0.

The images have been postselected for the correct particle number of the 6 + 6 ground state but are otherwise chosen randomly. The dashed circles indicate the Fermi momentum. All detected atom pairs with Δϕ < 30° and both p↑ and p↓ larger than 2/3pF are highlighted. These are the particles that would contribute to the pair-correlation peak at the Fermi surface (see Fig. 2f). Without interactions we find no additional pairs other than what is expected already from the single-particle densities. Considerably more pairs are present in images taken at larger interaction strengths (compare Extended Data Fig. 5).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Average momentum space distributions.

a, b, The mean momentum-space distributions n↑(p↓) of a single spin component and averaged over 1,000 images for two different binding energies and 6 + 6 atoms are shown. The dashed circle indicates the Fermi momentum. The distributions are to a good approximation radially symmetric. With increasing binding energy, the average momentum increases and we find more particles outside the Fermi momentum. This agrees with the picture that increasing the attraction enables particles to overcome the single-particle gap and form first Cooper pairs that finally turn into tightly bound dimers. c, From the average momentum-space distributions of both spin components it is straightforward to calculate the total mean kinetic energy of the system per spin component. For 6 + 6 non-interaction particles, we find a value very close to the expected ground-state (GS) kinetic energy per spin component of \({E}_{{\rm{kin}}}^{{\rm{gs}}}=7\hbar {\omega }_{r}\). The kinetic energy increases monotonously as the attraction strength increases. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. d, The unnormalized correlator \({{\mathscr{C}}}_{{\bar{p}}_{\downarrow }}^{(2{)}^{\ast }}\) is shown for EB/ħωr = 1.97. It is defined as in equations (1), (2) but without the ⟨n⟩⟨n⟩ term. It shows that for strong enough binding energies the paired fraction becomes large enough that pair correlations are visible even without subtracting the single-particle density contributions.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Alternative visualization of the density–density correlation function \({\boldsymbol{\mathscr{C}}}^{{\boldsymbol{(}}{\bf{2}}{\boldsymbol{)}}}\).

The pair-correlation functions in relative (\({{\mathscr{C}}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{(2)}\)) and centre-of-mass (\({{\mathscr{C}}}_{{\rm{C}}}^{(2)}\))coordinates as a function of the interaction strength EB are shown in a–e and f–j, respectively. The figure represents an alternative method of binning and visualizing the 4D correlation function \({{\mathscr{C}}}^{(2)}\), but is otherwise equivalent to the data shown in Fig. 2. The dashed circle indicates twice the Fermi momentum, 2pF. In relative coordinates (a–e), we find a surplus of particles with momenta of |pR| ≈ 2pF, as expected for the formation of Cooper pairs with atoms located at the opposite ends of the Fermi surface. In the centre-of-mass frame (f–j), emergence of pairing is indicated by a sharp peak at zero momentum that increases in weight with the interaction strength. k–o, Radial integrals of the relative momentum correlation densities in a–e. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Correlations in a heated sample.

We increase the energy of the sample by modulating the radial confinement with a pulse of 50 ms duration that is a square pulse of width 700 Hz in frequency space and with variable amplitude A (inset). We find that the pair correlations reduce with increasing energy of the sample until they vanish completely. This measurement was taken at intermediate binding energies of EB/ħωr = 0.6. In the future, we plan to study above-ground-state physics of our mesoscopic Fermi gas in more detail. To this end, we have to develop a precise method to measure temperatures of the sample. The error bars are obtained from the counts in each bin of the correlation function and by assuming Poissonian statistics.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holten, M., Bayha, L., Subramanian, K. et al. Observation of Cooper pairs in a mesoscopic two-dimensional Fermi gas. Nature 606, 287–291 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04678-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04678-1